One of the best things about coming home from a trip is being surprised by what’s been happening in the garden during my absence. When we left a fortnight ago, there was one wild terrestrial orchid plant just coming into bloom. Today, that first flowering stem has been joined by another, and the plant has now grown to a fat clump carrying lots of flowers and buds. And two other plants have come up nearby to keep it company.

Flor de l’Abella, Flor de la Abeja

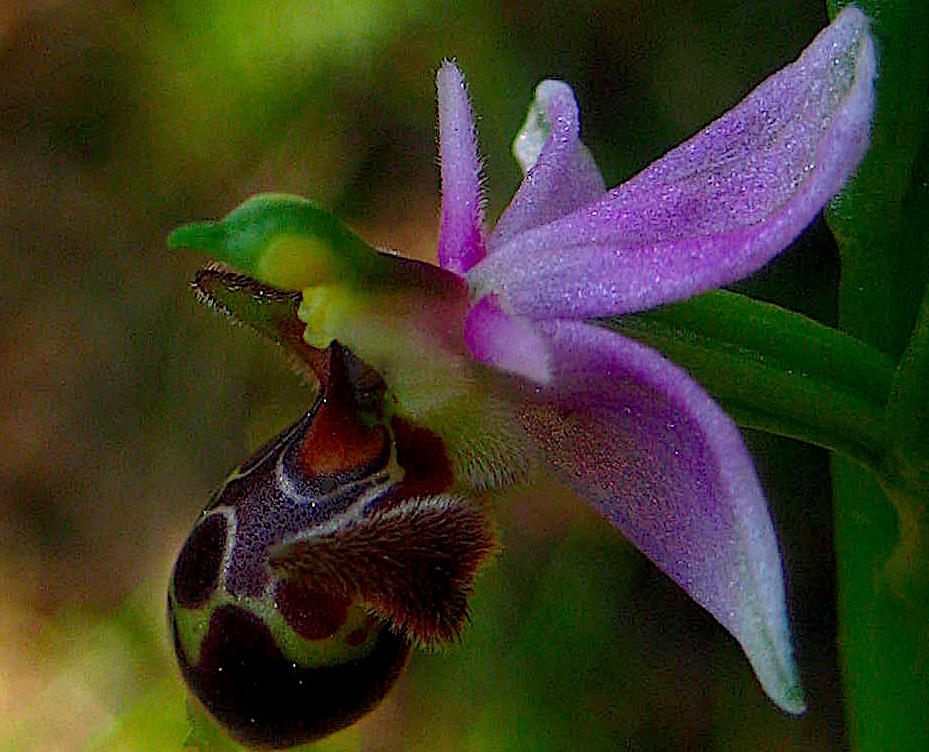

Discovering this endemic wild terrestrial orchid — Ophrys scolopax — flowering in my garden is such a wonder. And a reward as well. It appears that ground orchids are the canaries of ecology — they are to be found only in healthy ecosystems. I spied these mysterious orchids as soon as we moved in. For the past three springs, these beauties have graced one end of a terrace bounded by dry stonewalls. They don’t come up anywhere else, and the mystery is that they never come up on the exact same spot as they did the previous year. Where exactly within that approximately 3-meter-square area they will appear is an annual surprise that I await eagerly. Beyond their rarity and beauty, I adore these orchids because they always cheer me up. Who can fail to be amused and not try to match the infectious grin on this orchid’s face? And how about that adorable mauve top outlined in white, and the prominent belly button, jutting out from those cool chestnut brown trousers held up with a bow? And check out those cute socks!

I had called it “bee” orchid in previous posts because of its close resemblance to Ophrys apifera, but O. scolopax is actually known as woodcock orchid in English (Latin scolopax = woodcock). In Castellano it is known as flor de la abeja (bee flower), and in Valenciano, flor de l’abella. Rather confusingly, the book Orquideas Silvestres de la Comunidad Valenciana (Wild Orchids of the Valencian Community) gives the etymology of scolopax as partridge (perdiz), citing the similarity of the column (the fused male and female sexual organs) of O. scolopax to a partridge head and beak when viewed laterally (see photo below). Ophrys means “eyebrow,” and refers to the fuzzy curved “wings” surrounding the swollen lip or labellum. The O. scolopax found in my mountain hamlet is a subspecies known as O. scolopax Cav. subsp. scolopax. It differs from the principal scolopax species due to its backswept tepals.

and fuzzy “wings” surrounding the orchid’s lip.

The epithet “bee orchid” (yet another confusing terminology used in Spanish botanical guides) to refer to the Ophrys genus comes from its reproductive habit of sexual mimicry. That is, the flower presents as a female bee or some other closely related insect pollinator, enticing the male to approach and in many instances carry out pseudocopulation, in the process collecting and spreading pollinia (a mass of orchid pollen). The insect-mimicking orchid may also exude a scent similar to that of a certain female pollinating insect.

Photo: La Guia Botanica de la Vall de Gallinera.

Orchids are among the earth’s most diverse species, with from 25,000 species currently identified and regularly updated by the Royal Botanic Garden at Kew. Of these, the Ophrys genus is the most biodiverse of the European terrestrial orchids with 200 to 250 species, and is found in alkaline and acidic habitats throughout the northwestern region of the Mediterranean from sea level up to about 1500 meters above sea level, principally in Spain and Portugal, as well as Corsica and Italy. Some Ophrys species are also found in Scandinavia, the UK, and in the Atlas mountains in northern Morocco. Ophrys species can be found in all three provinces of the Valencian community — Alicante, Valencia, and Castellon — in montane grasslands and forest clearings (especially plentiful after forest fires), though not in semi-arid areas or those too close to the coast. Ophrys orchids in general start to leaf out in spring and flower from March until June, and survive the heat and drought of summer thanks to underground tubers. This year, perhaps due to the long interval between heavy rains (the previous one was at the end of October and the most recent in mid-April), the Ophrys orchids in my garden are only blooming now, weeks later than previous years.

I’d like to encourage these rare beauties to increase, and I’ve tried to interfere as little as possible with their surroundings, knowing that many terrestrial orchids have a symbiotic relationship with soil fungi. Over the past year, a low-growing (< 30 cm.) plant has spontaneously appeared throughout that part of the garden. Once identified as Dorycnium hirsutum, a nitrogen-fixer, I have let it spread to its heart’s content. Other plants that have also appeared on their own among the low-growing grasses surrounding the orchids are clover, a yellow-flowered legume (its name unknown as of this writing), and a mauve-flowered diminutive plant with narrow needle-like leaves that I have yet to identify.

However I’ve learned just now that for terrestrial orchids to flower and set viable seed, they need high light levels. In Europe, the traditional management of mowing grasslands once a year or once every two years, usually in mid- to late summer, enables terrestrial orchids to thrive and set seed. I shall have to closely monitor the height of these nitrogen-fixers and grasses to ensure they do not inhibit the spread of this extraordinarily cheering orchid.